The joys and pains of fatherhood — Happy birthday Dad!

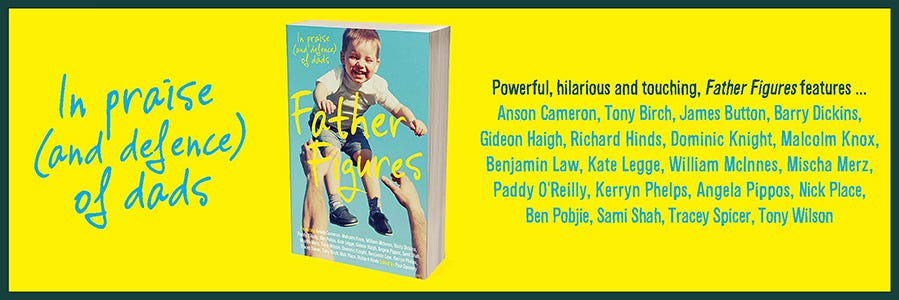

My father Ray turned 78 over the weekend. I contributed this piece to a book called 'Father Figures: In praise and defense of dads' in 2017. My kids now range from ages 16 to 7.

Sixteen limbs, twenty if you count my own. Sixteen limbs, four noses, eight cheeks, four of that little bit of neck that’s not covered by the rashie, eight ridgy, uncooperative kicking feet —just the bony bits that point up towards the sun. I draw a line at the eyelids. I say they need to blink quickly enough so that their eyelids won’t get burned, but my wife Tamsin, their mother, is an inveterate eyelid creamer. She’s also has a painting background, so after I make my pass, having emptied what seems like litres of SPF 50+ across acres of pale Wilson skin, she assumes position for the finer brushstrokes. Eventually, maybe five hours after the first slap of cream hit the first reluctant leg, four distraught, strung out kids are sun-ready and raring for the beach! If we can just find Harry’s fucking goggles ...

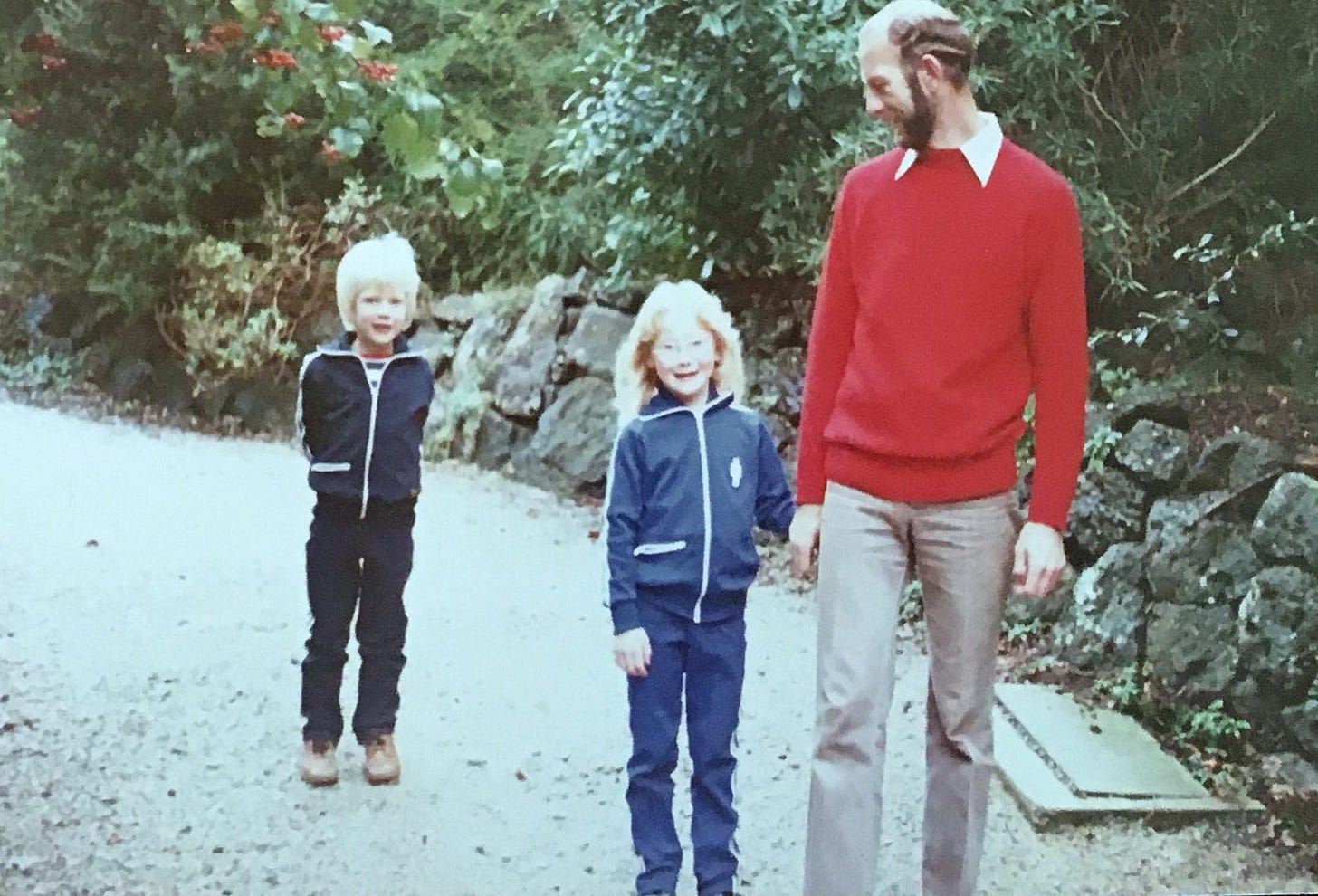

I remember my own father’s sunscreen Waterloos. We were also Wilsons, also four in number, also girl, boy, boy, girl —luminously pale. Back then, SPF 50+ was the stuff of science fiction, and Ray Wilson made do with SPF 15+, roping us, his reluctant progeny, against beach house furniture like it was the Calgary Stampede. Mum was not trusted with suncream. Dad always whispered about SPF sins in Mum’s past. She was too much of a dauber, not enough of a slapper. Whole limbs had been left off the itinerary. She was occasionally cavalier with SPF 8. ‘You see your mother has olive skin. She doesn’t understand any of this. You can’t make mistakes out there. You’ll be cooked red raw. Red raw!’

I never say ‘red raw’. Nor do I say ‘burnt to buggery’ which was another of Dad’s infamous alliterations. Instead, I wail my way through these slippery ordeals like a screaming fighter jet. ‘Do you realise what the sun can do? It can cook your skin right off. You could end up in hospital! None of you have even been properly burnt! Polly, get off your brother! Harry, where are your freaking goggles!’

Dad was calmer, I’m almost certain. My own theory is that parenting was easier in the era of the permissible smack. My parents didn’t do it often, but the threat hung there in the air, not to be scoffed at like my own feeble ‘we’ll take away the iPad! I’m serious this time! No screens for a week! No, seriously! I could not be more serious this time!’

The truth is that I’m guilty of the very occasional smack. But guilty is the right word. We live in Northcote, the beating heart of Melbourne’s gluten-free belt, and to smack in these parts is akin to sewing poppets in 16th century Salem. I always try to aim below the knees, open hand, and I know I’m in more trouble than the kids if I leave a mark. Tamsin’s rule is, never smack when you’re angry, and I’ve obeyed this rule exactly zero times. ‘She kicked me in the nuts, Tam! What am I supposed to do, just take it?’ To think my parents had The Wooden Spoon! It’s decades now since wooden spoons have been allowed to have capital letters. You can find The Wooden Spoon on Wikipedia listed amongst medieval torture devices like The Cat o Nine Tails and the Judas Cradle. This is a good thing, I know. It just means that I shout a lot.

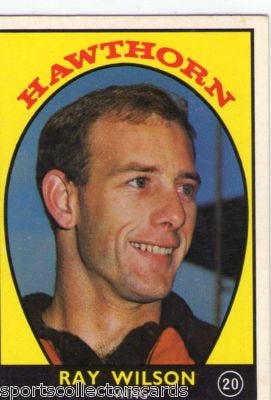

I wonder if it’s the same for most fathers. That the word ‘fatherhood’ is a contrapuntal melody played out in two parts, the first being that of being fathered, the second that of doing the fathering oneself. For me, the melody being played by the first hand is a sweet one. It was wonderful, and still is, to have Ray Wilson for a dad. I was born when he was drawing stumps on two careers, one as a high school teacher, the other as a VFL footballer with Hawthorn. He was starting a new financial services business in the early to mid seventies, one which would eventually succeed in spectacular ways, but I know now that these were tough times for Mum and Dad. Dad worked in the city, he commuted at least an hour each way. He couldn’t have had enormous amounts of time for parenting. Mum held the fort at home with two pre-schoolers. Certainly, my own creative arts career has allowed more flexibility. My kids have seen more than me than I did of my father.

And yet my early memories of Dad rise like champagne bubbles. He was a physical dad who played with us constantly. He gave us piggybacks, tickles and what we called ‘whizzies’, which are those round-and-round spinny things you do at the cost of feeling sick yourself, just to hear the music of your toddler’s laugh. He read us nightly stories. I remember walking Wilsons Promontory on summer holidays, recoiling in fear at the dried-out banksia cones that dotted the tracks around Tidal River — because the Big Bad Banksia Men were Snugglepot and Cuddlepie’s nemeses in Dad’s bedtime reading. I remember squeaking the sand with him, swimming on his back, and rolling down the dunes. He sang us songs at night, ‘You’re always going to be my little baby’, which I haven’t googled but I believe may be an original composition. I remember him making billy carts, actually buying wheels and ballbearings and constructing a box racer like some sort of American TV dad, which is all the more impressive given what I now know about Dad’s handiness or lack thereof. A general feeling of unease walking through the doors at Bunnings is something we still share as father and son. I remember Rafael, our pet rabbit, dying on his lap after a dog attack. I remember marathon tennis matches, which I regularly won 7-5 in the fifth, despite having half his height and half his talent. I never suspected a thing.

But what we really shared was football. Dad’s status in my childhood universe as an ex-VFL footballer was immense — he was a Best and Fairest winner at Hawthorn, a premiership player in the club’s second flag. During my childhood, he volunteered as coach of the under 17s Peter Crimmins Squad. On Sundays, we’d venture to the glorious, liniment scented bunker at Glenferrie Oval, where we’d be welcomed into corridors other kids couldn’t go. Leigh Matthews, Don Scott, Peter Knights, these gods that I worshipped on TV actually knew my dad! Were friends with him! I’d eat sausages in the trainers’ room and play with the kids of footballers, even luckier kids whose dads still played. The boot studder called me Snowy. I helped Andy clean the boots in exchange for barley sugars. On Saturdays, we could go to our seats via the rooms and watch the Hawks warm up. ‘One two three four five six seven eight nine ten!’ they’d roar, and then smash into each other’s enormous oiled-up arms. I knew what I wanted to be. I never had any trouble knowing what I wanted to be.

Dad encouraged me the whole way, and it almost went the whole way. I wasn’t allowed to play until I was ten, that was one of his rules, but after that it was a shared obsession. Endless hours were spent playing kick-to-kick, practising footy, talking footy, talking generally. At dinner time, Dad would discuss exactly where I should run to make good position. The salt and pepper shakers were usually drawn into the analysis.

I was drafted, a father and son pick for Hawthorn in 1991. The AFL Media Guide was brutal in its single sentence assessment - ‘perhaps a touch slow’.

Dad had seen this with his own eyes, and tried to help find me a yard. I had a sprint coach that summer, working on the knee lift that would later win me the nickname ‘Hymie’, in honour of the low knee-lifting robot in ‘Get Smart’. He encouraged me to join an athletics club, striving to counter that curse of the modern footballer —slow twitch fibres.

It was high-octane, super-involved parenting. I’ve since heard less flattering assessments from others who were on the outside looking in. Some people observed that Dad was pushy, or over-involved. I never felt any of that. I inhaled it all, grateful that somebody else had woven himself into this endeavour. That my dream had become our dream.

I was delisted without playing a senior game. In a shattered haze, I disappeared overseas to Quebec for a semester of university, to get away from footy, from Australia. Dad wrote to me frequently during those months, and I kept a lot of the letters. One was a beautiful half page saying simply that he couldn’t have been prouder of me for my footballing efforts.

He said something similar on the night before my VCE English exam. We were out running on Mont Albert Road at eleven pm, because I’d been too nervous to sleep. ‘It doesn’t matter how you go —I’ve seen the effort you put in. You made your decision about tomorrow in January.’

When he saw I was miserable as a commercial lawyer, he took me out to lunch to ask me what career might make me happier. ‘I think I want to be a writer,’ I said. ‘Well for somebody who wants to be a writer, you don’t seem to actually do any writing,’ was his useful reply. A year later, a failed travel manuscript had morphed into my big media break, a place as one of the eight young travelling filmmakers on the ABC documentary making show, Race Around the World.

When I had my idea for a footy media satire in 1999, I told Dad. For four years, he bugged me to write it. ‘Write it. Somebody else will have the same idea. The Footy Show surely can’t stay on air forever. Write it!’ Eventually I did write ‘Players’ and it was a bestselling and award winning novel. Would I have written it without him? Possibly. Will The Footy Show actually ever die? Never. [update: this sentence might have single-handedly done it in]

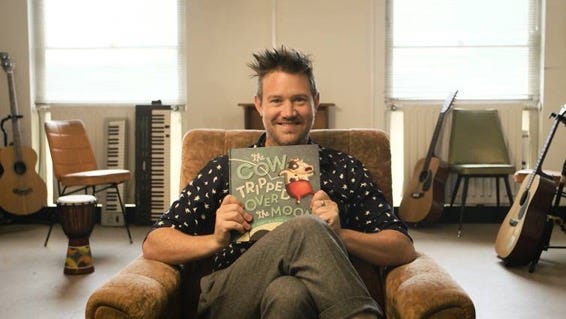

Even last year, when my eighth picture book ‘The Cow Tripped Over the Moon’ was honoured by the Children’s Book Council, Dad sent me a text: ‘Fantastic effort. I have never doubted your talent. Congrats. I am very proud of you. Dad’.

Champagne bubbles rising over forty-four years [update: 50!!]. It’s undeniably rose-coloured champagne too, because the wash of years has rinsed away the fights, the nagging, the endless scroll of mornings and bedtimes, all lost as part of the unremarkable beige of suburban history.

For me, the experience of being a father couldn’t be more present or demanding. Tam and I have four kids under eleven, Polly, Harry, Jack and Alice. My brain currently swims with moments that will no doubt be lost as part of my own children’s unremarkable beige. Polly, 10, dropping frozen raspberries on the kitchen floor every time she makes a smoothie. Right, no more smoothies until you learn to clean up! Harry, 7, still playing Roblox when his swimming lesson starts in five minutes. Where are your bathers! Harry! HARRY! You must be able to hear me! Alice, 2, refusing to sit on the potty but not liking to wear a dirty nappy either. Oh my god, she’s slid all the way down the stairs! Tam! Code Brown here! Tam! Jack, 5, asking for a new Bruce Springsteen track on his iPad every two minutes. Please Jack, just listen to the whole song! We just changed it. Why can’t you listen to the whole song?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Good one, Wilson! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.