It’s a South Melbourne FC special event — juniors, past players, parents and the broader South community will be there. And there’s Q and A afterwards, with me and Cam and four of our favourites in the doco, Paul Trimboli, Miki Petersen, Kimon Taliadoris and Gus Tsolakis. So basically it’s the best day of my life, premiere day a month ago, reduxed!

You can come too if you like. We have three more screenings before Christmas, this one, and then two more QandAs at the Thornbury Picture House on the 5th and 21st of December. The Thornbury ones are pretty much sold out, so tomorrow is the hot ticket!

We had some lovely press for Ange & The Boss, back in the before times when we were trying to get it released and it was still called ‘Puskas in Australia’. Basically, with the Ange ascendancy happening before our eyes, English journalists were so hungry for Ange content that they tracked us down.

My favourite of the 2023 articles was one in The Times by James Gheerbrant. Here it is, in case you missed it last time:

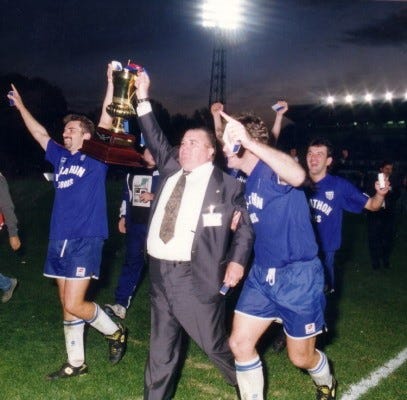

South Melbourne have just won the 1991 national championship and the trophy is hoisted, together, by Postecoglou — beaming, tousled, sporting a yacht rock moustache — and Puskas — proud, grandfatherly, splendid in his capacious suit.

Nothing in football conducts like silver and it's an amazing thought that the electricity of that moment, the charge that passes between coach and player, connects Hungary's Golden Team who famously vanquished England in 1953 and the team who, 70 years later, sit atop the Premier League table.

When the Magical Magyars visited the old Wembley in 1953, English football was at once imperial and insular: thinking of itself the cradle of the game and ignorant of the extent to which football had been embraced, embedded and improved upon in other countries.

By the late 1980s, football had few worlds left to conquer, yet Puskas, in his sixties, set out for one of them. He went to Australia to run some schoolboy training camps but through his links to the Greek community — he took Panathinaikos to the European Cup final in 1971 — found himself coaching Hellas.

Although he spoke scant English, he carried with him a vision of what the game should be, which, almost 17 years after his death, one of his players would carry back in the opposite direction, from football's new world to the old.

This is a good moment to understand Postecoglou better, as his impact since arriving at Tottenham has been transformative — not simply in performance but also in mood and tone. There may be troubles ahead. Recording 2.5 points per game cannot last. Given the loss of Harry Kane, the strength of Manchester City and Arsenal, the resources of Chelsea and the resurgence of Liverpool, a top-four finish still feels like a tall order. At some point, injuries will bite and clouds will mass.

But for now, the capacity of this well-travelled, middle-aged manager to win football games and make a downtrodden fanbase feel inspired again has been one of the most fascinating parts of the young season.

Postecoglou has spoken before about the influence of playing under Puskas, long car journeys spent teasing ideas out of the great man like spun gold, the broad-brushstrokes tactical philosophy that he imparted: two wingers, full backs flying forward, an approach tilted towards attack, adventure and abandon.

Really, though, what the film shows is that any instruction Puskas passed on to his players was feather-light, far outweighed by his sheer joy and infectious belief in a style of play that was positive, open-hearted and entertaining. Any cynicism was instantly vaporised on contact with this far-flung comet of football gospel.

Some of the vignettes of archive footage are simply delightful. We see Puskas taking training in a black tracksuit with the word "BOSS" emblazoned on the front and a whistle around his neck. Puskas giving an entire stadium of home fans the bird after they chant for him to bring a popular substitute on. Puskas playing in an amateur game on some rutted farmland pitch, carrying his prodigious stomach with the upright majesty of a ramrod-backed marching-band major carrying his bass drum, caressing 50-yard passes and smoking half-volleys into the top corner with minimal effort or flamboyance.

The vibes, as they say, were immaculate. And this is what comes through above all in the depiction of South Melbourne Hellas at the straddle of the 1980s and 1990s: just how much fun everyone seems to be having, even as they chase aims and titles that feel hugely important to them. "Those were the best days, those were the best times, playing in front of our fans, it gave people a lot of joy and a lot of pleasure," says Kimon Taliadoris, one of Postecoglou's team-mates.

It's not hard to trace the lesson of those years in what he is creating now. Some of Postecoglou's vaunted predecessors as the Spurs head coach acted as if this game has to hurt you and make you suffer to mean something — that it is only in that collective endurance that the bonds of a winning culture are forged. The present Tottenham head coach knows that meaning, togetherness and unity can also be drawn from your best days, not only your hardest ones.

"He made a really caring, strong environment where people cared about each other, about him, and didn't want to let each other down," Postecoglou says of Puskas.

"Having a dressing room which cares about something beyond the result, you can create something special, and that's what he did.”

The film is a vivid portrait of a moment in time but also a fascinating document of the immigrant experience. I had not realised how closely Australian football, in Postecoglou's playing days, was tied to it. So many clubs represented a particular migrant community, from Hellas and their rivals Melbourne Knights (Croatia), to Marconi Stallions (Italy) and Wollongong Macedonia.

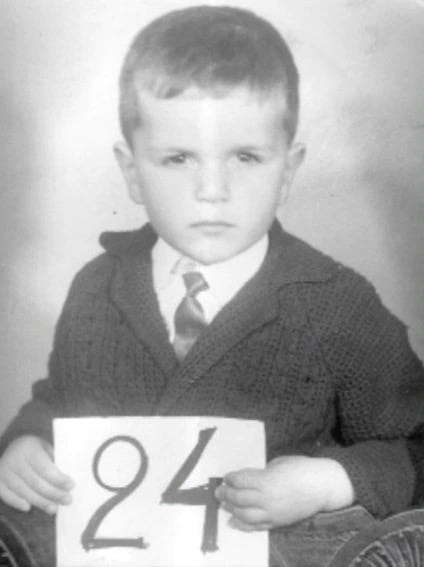

We see 1960s newsreel film of a vast white steamship sidling into Port Melbourne bearing its cargo of uprooted lives. Thronged passengers in suits and hats peering over tall gunwales as a strange continent slides into view, wind-ruffled men and women walking down gangplanks with their worldly possessions held in suitcases and knapsacks, little boys in short trousers and buttoned coats holding the hands of their younger siblings.

There is a poignant photograph of a five-year-old Postecoglou, fresh off the boat, wearing a cardigan and tie, holding a card on which the number 24 is written.

"We didn't speak the language, didn't know a soul, no guarantees about income, housing, anything," he remembers. In those circumstances, Hellas "wasn't just a football club, it was a sanctuary from the tough times my parents were going through from Monday to Saturday. Come Sunday, particularly my father, as soon as he walked through the gates and the smell of the souvlaki... my dad just became a different man.”

Most Premier League head coaches have, from a young age, built their lives on football.

They have constructed monumental careers, from which vantage they look down, as if from a glass-paned observation deck.

Postecoglou's life — certainly his early life — on the other hand, was built around football: the game was the nexus for social and familial connection.

If he is different, perhaps it's because he knows not only the game's height but also its reach. He grasps not only its magnitude but also its centrality. Whatever the future holds, the Premier League feels richer for his presence — in the same city where Puskas first shocked the world.

Share this post